AI, Data Centers, and Our State

What the growing data center economy means to me, a Wisconsin resident planning for the future.

This post is best viewed in the Substack app, it’s too long for email.

Charlie Berens, of Manitwoc Minute fame, recently took a stand against the planned Vantage Data Centers project in Port Washington. It got enough traction to warrant local news interviews of the comedian and the Mayor of Port Washington, Ted Neitzke. Since those stories ran, Vantage, Oracle, and OpenAI announced that the planned investment of $8,000,000,000 will increase to $15,000,000,000 for four data centers. As part of the Stargate initiative, project “Lighthouse” is planned to bring in over 4,000 construction jobs and about 1,000 permanent jobs related to the data center management. There are serious consequences for this level of investment.

There are a lot of questions that remain unresolved, at least in contractual, binding agreements. Who is going to pay for the infrastructure? How are we going to make the electricity needed to run the data center? How many jobs will this actually create? Do we want this?

As a Wisconsinite of 8 years and someone who plans to be here for decades, I decided to take a deeper dive into what all this means for us and go beyond what headlines, press announcements, and social media want us to know.

Foxconn left deep wounds

The first thing to understand about tech investment in Wisconsin is we’ve been here before. In 2017, Foxconn announced over $10,000,000,000 in investments to build “Generation 10.5” electronics in Wisconsin that paired with 13,000 jobs. Those billions turned into millions and tens of thousands of workers ended up just over a thousand. While most of the $3,000,000,000 in tax credits were performance-based and were unrealized, the state still invested too much into a company that failed to realize its promises.

So when Charlie Berens focuses the discussion on billionaires using our farmland, our water, and our state to make their anticipated trillions:

AI revenues growing to hundreds of billions may seem extreme, but if AI could improve productivity in a significant fraction of work tasks, it could be worth trillions of dollars.

I understand why he’s concerned. The story goes: a couple of executives at these AI companies decided that the areas that are not in their backyard can host the infrastructure needed to generate their massive profits. They’ve distanced themselves by thousands of miles if there are any tradeoffs to these projects and technologies, once again leaving Wisconsinites on the hook. State lawmakers and local politicians have welcomed these projects through tax breaks, even when their constituents oppose the new developments. No one can stay on top of every update, every news release, and every deal made behind closed doors or under (alleged) NDAs. When they do, constituents show up frustrated at city meetings and make their case to not build it. The city “hears” their concerns, but pushes forward anyway and the construction occurs as planned.

Already, I can see that the estimate for permanent jobs is problematic. Even though the AI companies estimate over 1,000 jobs, reporting and city FAQs put this closer to 200-400 jobs (50-100 jobs, 4 buildings)1.

I want to make sure this story is accurate and what we can all learn from this process. This hits close to home as a data center proposed for Vienna (30 minutes north of Madison) could potentially consume 2.5x the energy consumption of Dane county.

Who’s paying for all this electricity?

The most important story for residents likely resolves around payment for these projects. As electricity costs go up in the U.S, many are starting to look at these AI data centers as a potential source for the increase. They are often described to be guzzling water and resources (like this commentary here) to the tune of maybe 6,600,000,000 m³ of water by 20272. That’s equivalent to 1,743,500,000,000 gallons, or about 90% of water used by Wisconsin residents and businesses annually. Not to say it’s not a lot, but if the entire AI industry uses a state’s worth of water and it can cure cancer or generate trillions in revenue, maybe it’s worth the cost (and you just tax it more efficiently)? It’s a big maybe, but I can understand how lawmakers may come to the conclusion that they want that infrastructure being built here so the money flows to Wisconsin.

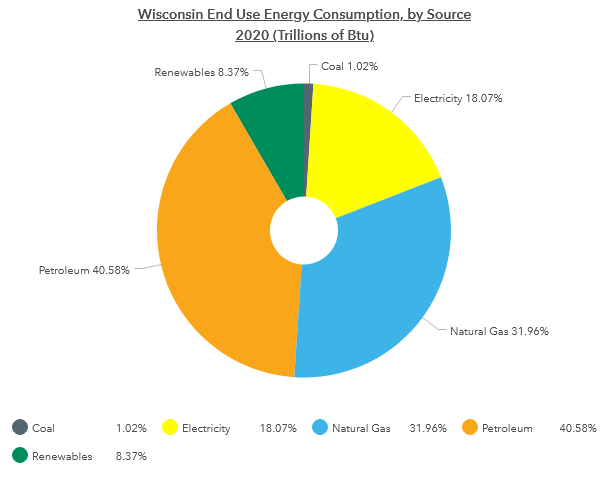

A separate consideration that I think most lawmakers are debating currently is the stress on electricity prices. It’s not as simple as looking at the Public Service Commission’s (PSC) energy statistics dashboard and grabbing the “electricity consumption totals” from the highlights of end use energy consumption to focus just on electricity:

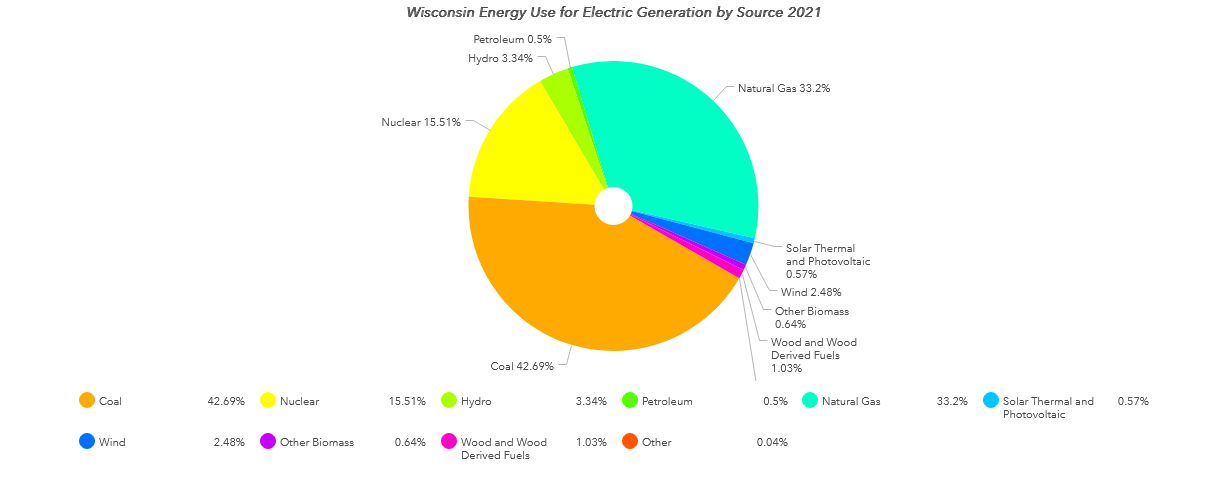

We have to be careful, because this is 2020 data3, but this would account for about 67,500,000 megawatt hours (MWh). If we steer over to the highlights on energy use for electricity generation, we can see a mix of sources produce the amount consumed above:

21,000,000 MWh of electric generation in Wisconsin (in 2021) came from natural gas4. Many sources of energy contribute to electricity usage and introducing a large demand would likely increases the price for all forms of energy generation. It isn’t as simple as “solar” or EVs, even gas plants could experience price hikes.

The price for that electricity was 14.32 cents per kWh in 2020. I believe it’s around 18-19 cents per kWh today (and MGE puts it at 18.4), which would be valued at $12,500,000,000 for the 67,500,000 MWh of power. The Port Washington project is expected to need 1,300 megawatts of energy. I expect this facility would run 24 hours a day for the entire year, putting an annual load of 11,388,000 MWh or about 17% of the entire state’s electricity usage. That’s a ton of energy that the state (and it’s residents) will need to contend with. Who will pay for it?

The obvious answer is to require the data centers to supply the power themselves. But of course, if it’s going to cost you $1,700,000,000 a year in electricity costs5 to run your data center, you’d love to pass it on to the other consumers. If you can convince the PSC that this infrastructure is worth building, and the utility companies agree because they are able to raise prices when they invest in infrastructure, you’ll reduce your costs and you won’t have to worry about the residents from your compound in Silicon Valley or Lake Tahoe.

Vantage appears to be paying a dedicated electricity rate to We Energies (the utility that would be responsible for providing the electricity). But I personally would like to see that contract in writing. Is this for in perpetuity? What happens if there’s additional investment? Can the utilities go to the PSC and say that the infrastructure costs should allow them to raise rates? These are the numbers that we should be throwing around when we discuss the project’s merit. Any future projects in Wisconsin should go through the same process and ensure that the AI companies are treating electricity as a cost of business for their bottom line and not passing it along to constituents.

What are the cities giving up?

Many constituents fear the light, noise, and construction pollution that comes with developing around 1,900 acres of land. What causes mayors and city councils to seek out this investment?

The common answer is the jobs. Just like Amazon’s HQ2 search, where cities fell over each other trying to lure 25,000 high-income workers to their city. The data centers promise high-income workers to maintain the servers and that income can be a boon for the community. The workers will buy homes, pay taxes, and buy from local businesses to help sustain or grow the economy.

I think this conventional wisdom misses the key reason a city in particular wants large investment that’s not residential: a wealth of property taxes.

We still pay for the sins of Scott Walker: in 2011 the state legislature increased restrictions on levy limit increases, limiting growth to the “net new construction” in a given year. If you want to learn more about levy limits and how municipal finance works in Wisconsin, please give Erik Paulson a read.

It forces municipalities to constantly build to maintain current services or to go to the voters to get levy limit increases (effectively property tax increases). Cities should be building, but established cities like Madison are not going to be able to build 10% of their existing city in a year in an attempt to keep up with inflation. Inflation hit cities hard; 23 communities went to the voters in 2024 to raise taxes.

When a business approaches you and says that they are ready to build a multi-billion dollar facility and that you can assess the land for $120,000,000 by 2027 before the construction has even begun, it’s hard to say no. Port Washington had a total equalized value of $1,720,339,200 in 2024.

Net new construction can be realized in Tax Increment Districts (TIDs) as they are built. In 2023, the State passed new laws surrounding TIDs that allows for municipalities to realize only 90% of new construction value in their levies (although removing the “net” aspect of it). The city estimates “approximately $650,000 per year in new tax revenue” (about 6.3% of their total revenue) will be introduced beginning in 2027. Presenters at a city meeting discussed balancing increasing levy limits with new gains in value. If this doesn’t make sense, it’s because the new assessed value would allow the city to increase its levy by 6%. Immediately levying that 6%, despite the new taxpayer in Vantage, would likely increase property taxes city-wide. As the property develops, there will be more “levy” opportunities, but the city will not be able to maximize these (without forcing higher taxes). Instead, it sounds like they will use state statutes that allow them to “carryover” up to 5% of the increased levy capacity over five years to help spread the increases out (in addition to whatever they do end up levying). When the TID is complete (we will get to that shortly), the entire value of the project will be realized as a taxable asset, but the City will not have used all the levy capacity it generated (for fear of taxpayer revolt). When the levy is determined, the levy is spread out equally (per the Uniformity Clause) to all taxable property at a mill rate per thousand dollars of value. This huge project, if it realizes the $1,200,000,000 expected property value at completion, will make up potentially a third of taxable property in Port Washington and would take on a third of the property taxes in the city. This is the benefit that city officials try to convey to the constituents; “property taxes keep rising, what if we brought in a big property owner to help shoulder the burden?”

The tax increment financing district also covers the city infrastructure costs of the project. The TID will use a baseline property value that will remain at this value until the TID is paid off or twenty years lapses. Property taxes will still be paid, they just won’t increase as the land is assessed for more value (the levy can still increase though). When the property value increases under the TID, the entity paying for the infrastructure can receive reimbursements out of the forgone taxes. When Vantage says they will front the $175,000,000 in city infrastructure (water treatment, water tower, sanitation, sewers, roads) that the city would typically pay for, they are receiving this money on a deferred loan. The city is taking on debt, in the form of a loan from Vantage.

Is this good for the city? It depends. Do you believe this project would have been viable without the tax incentives? With the money being thrown around for these data centers it sounds like some entities could cover the loan themselves. Typically you want to fund projects that the private market will not invest in (like affordable housing) rather than projects that they will invest in. Cities have limited resources and putting it into something that could have existed without your support is a waste.

It does make Port Washington seem like a good partner, but from a constituent’s perspective I don’t necessarily want the city to sell themselves out for a project that has some risk associated with it. If you listen to the presenters in this work session meeting, you can hear them talk about this project as if Vantage holds all the risk of the investment. Vantage would cover the initial assets, but what if the data center couldn’t find clients? The city would pass on 20 years of property taxes and would be left with maintaining a hundreds of millions in serious infrastructure investment. Vantage does not “hold the entire bag” for this project; the city is a part of that bet and residents are right to question it.

What about the noise?

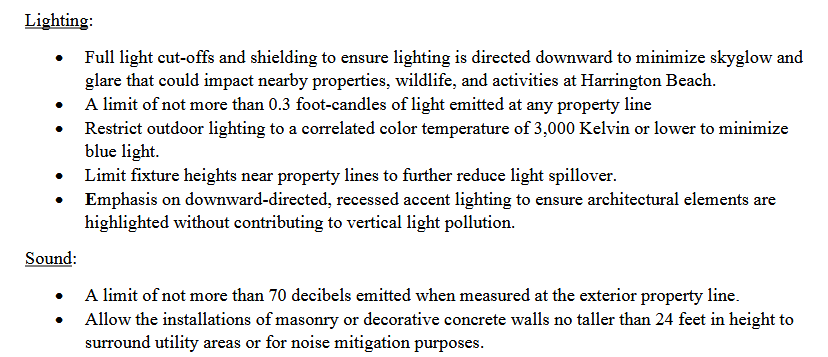

I think the most serious complaint that residents have is the pollution these facilities generate. The buildings are lit 24 hours a day and they are loud, ranging from 75-95 decibels. Madison is familiar with noise pollution, as fights drag on for funding to reduce F-35 noise pollution near Truax Field drag on. The “incompatible” average noise level threshold for residential areas is 65 decibels.

Port Washington uses one of my least favorite residential tools to handle an appropriate use for industrial cases: zoning. As part of the rezoning process for the land, there are lighting and sound requirements for the area:

If I were a resident I would be pushing for and compromising on stricter restrictions. Taking the city at their word that the investment is sound/a risk worth taking, we should focus on reducing externalities that residents will have to face that the investors and owners of the data center will not experience. Taxes work great and the city can “tax” them into stricter zoning compliance that forces them to invest into better pollution-mitigating infrastructure. And in our highly litigious society, you betcha I’d post up on that “exterior property line” and measure every day to try and find moments where 70 decibels were exceeded. Zoning is a highly effective tool to reduce the construction of “annoying” buildings. In this case, if the building is polluting too much noise and light, that is a perfectly valid reason to revoke permits or cease operations until the pollution is limited. Make it clear from the beginning and strictly enforce it.

Who do we blame if this all goes wrong?

The obvious answer for blame resides with the state legislators who passed a law incentivizing data centers to be built in Wisconsin. We’ve discussed infrastructure and land, but that covers less than 25% of the expected property value for Port Washington. A lot of it is going to be servers and equipment. Per 2023 Wisconsin Act 19, projects meeting investment and population center criteria are exempt from the sales taxes for the storage, use, and consumption of tangible personal property used exclusively for data center operations. The Wisconsin Department of Revenue estimates that the exemption of a “typical” data center project will see a sales tax decrease of $8,500,000 for the initial construction and about an ongoing $1,000,000 decrease in revenue. That and cheap resources is what is incentivizing companies to build here.

The state legislators who introduced Assembly Bill 302, “An Act to create 77.54 (70) and 238.40 of the statutes; Relating to: a sales and use tax exemption for data center equipment or software”, are Representatives Zimmerman, Wittke, Allen, Armstrong, Binsfeld, Green, Krug, Murphy, Nedweski, O’Connor, Petryk, Pronschinske and Rettinger; cosponsored by Senators Quinn, Bradley, Cowles, Feyen, Nass and Wanggaard. To save you clicks, these are all Republicans and they include leadership positions. When this legislation was pulled into the overall budget package, only two Democrats voted for it (Madison and Clancy, both from Milwaukee) and no Republicans objected to it. Governor Evers (D) signed the law, with some partial vetos, but would have faced a Republican supermajority in the Senate and near supermajority in the Assembly.

I wouldn’t be surprised if this became a campaign trail issue as we approach 2026. Republicans will likely come out in support of their previous legislation, but I don’t know where the Democratic candidates will land as the primary commences. Some will clearly see this as an environmental issue (even if it’s overblown), others will look to the jobs angle that Berens hits hard on, but some might see this as a necessary investment to maintain healthy city finances until the legislature can work to increase shared revenue. It will be interesting to see if animated local government meetings spark into any kind of statewide backlash.

What’s next?

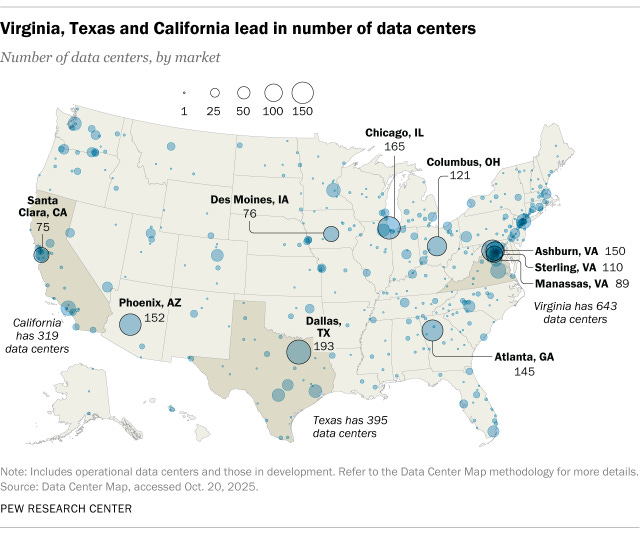

We might be in a bubble. We might not. The financing for these data centers is tremendous and I don’t see it going away anytime soon as long as the investment remains steady. Wisconsin will continue to be a place where data centers are built if we keep incentivizing companies to build here. We aren’t even the most popular place to build:

Legislators have the greatest control on the knob of investment. If I were in the Capitol building, I would be asking the following questions:

Will data centers be responsible for building their own capacity and infrastructure to connect to the grid, such that utilities will not raise electricity prices on residents? How do we codify this into law?

Will the energy capacity be completed with lower emission facilities6 and what barriers do the State need to remove to get this capacity on line?

Should the state enact strict pollution laws, such that entities in one location can’t construct a data center on a border and produce externalities for residents of the neighboring entity who had no say in the construction process?

Are we creating bad incentives for local governments and should we resolve underlying issues so governments don’t take risky bets like Foxconn?

In my mind, there are too many unknowns to definitively come out for or against these data centers. I think the best thing we can do is to hedge: don’t over invest, don’t rely heavily on debt, don’t build without ways to mitigate the externalities. Hopefully we don’t get a Foxconn 2, and if we do you’d hope the third time’s the charm and never again.

At least for the data centers themselves, I can’t say if the original estimates included unrelated jobs because of the expansion

You may have noticed that I type out large numbers. I think we’ve lost site of what million, billion, and trillion really mean; I want people to see the zeros

Why don’t we have more recent data? Your guess is as good as mine. It comes from EIA which is kept up to date

EIA estimates that it’s around 26,000,000 MWh of natural gas for electricity usage in 2024. Total electric generation is around 65,000,000 MWh.

Assumes an 20% discount on commercial energy prices, so 14.8 cents/kWh x 11,388,000,000 kWh

Like solar and nuclear, but also gas if the option is gas or coal