Abundance, Strong Towns, and the Comp Plan

We have until 2028 to start building default permission into our Comprehensive Plan.

Madison is a prime, lower tier suspect for Abundance, a book about our 21st century ability to expertly identify problems in society without the ability to implement solutions. Tailored towards progressives and liberals (who overwhelm the Madison political spectrum), the book challenges the status quo and the government’s ability to take on the challenges of our time: housing, climate, and immigration. It isn’t a question of how to resolve these problems; there are many solutions that exist. Far too often in liberal cities there are old laws designed to protect its citizens and the environment from previous dangers. These laws now prevent governments from helping citizens and the environment in a transformed world. Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson say now is the time to transform these institutions, build state capacity, and build an abundance of housing, energy, and economic development.

Charles Marohn, the founder of Strong Towns, challenges this assertion in The Trouble with Abundance. While Strong Towns and Abundance both identify the dysfunction of local governments, Abundance only moves the problem further up the chain via state and federal preemption. Strong Towns is a “bottom-up” revolution that relies on community members to observe where in their community someone is struggling, determine what small action they can take to address the issue, take that action, and repeat until you’ve incrementally solved your community’s problems. It’s empowering and helps build networks within communities.

The issue tends to be that individuals or small groups can only get so far before larger institutions (governments, commissions, boards, neighborhood associations) say “No.” and the solution can’t be implemented without a long, tiring fight. Strong Towns is the practice of patience and many feel these issues are too large and urgent to be patient when finding solutions.

I’m in the middle on this. I’ve been a member of Strong Towns since November 2022 and I really love the idea of building prosperous and resilient cities from the ground up. I also have Word document on my college laptop labeled “Growth Party Platform”, written in October 2021, discussing my ideal Ice Cream Party goals.1 It was frustrating to see Chuck express “unease” with Abundance, but in a world of short attention spans, it’s easy to equate “unease” with rejection when that isn’t the case. This is similar to the Escaping the Housing Trap, which explicitly referenced the YIMBY movement, its similarities to Strong Towns, where it diverges, and how it’s good to have these movements as separate entities. I was happy to come across We Can Have Nice Things by Stephanie Nakhleh and her clarifying dialogue with Chuck about a similar story between Abundance and Strong Towns.

Stephanie starts by expressing confusion over Chuck’s “competitiveness” and “conflict” in his criticism that she doesn’t believe needs to exist; both Strong Towns and Abundance’s visions “overlap” in a way that should benefit both groups. She also highlights that Chuck has stated that “most public input is ‘useless’ ” and that seems to be at odds with the Strong Towns ethos of “re-localizing decision making.”

Without knowing what Chuck is thinking, I can understand the goal of trying to define Strong Towns in ways that makes it impossible to co-opt it. He’s defending it from others who might misconstrue or bend support towards their own goals. Based on other interactions I’ve seen, I think he’s aggressively protective. These five campaigns are nonpartisan in ways that draw fire from both sides. If I were him, I would be defensive and I think this is his way of trying to ensure Strong Towns’ path to prosperity isn’t pushed to the side by other movements.

Chuck responds by defining Strong Towns’ core process (re-localizing decision-making and financial accountability) and the similarities and differences between the two movements. He has some great points about what good community involvement looks like, the traps Abundance may fall into, and how he thinks governments should approach enabling prosperity.

On community input:

When I talk about re-localizing decision-making… I mean restoring local systems that are capable of acting on community values, not just responding to noise… Right now, our local governments are overbuilt for input and underbuilt for action. Everyone has a chance to speak, but nobody feels heard.

On the trap of centralized power:

When Klein and Thompson talk about breaking local veto points… I get nervous when that critique turns into: “We need state-level mandates to bulldoze through the mess.” Because then you’ve just centralized the power again, only now it’s more brittle, less accountable, and often even further removed from the nuance of place.

On building systems:

I’d say: work to shift the default. If you have a comp plan that says “more housing,” then the next step is to reform your code so that small-scale, by-right development that aligns with that plan doesn’t need a permission slip every time. You’re not ignoring the neighbors, you’re respecting their voice in the plan, not privileging it at the podium.

This all leads me to the first (of probably many) screeds against the practice of law.

Should a city be able to build if it says it should build?

Earlier this month Dane County Circuit Court Judge Rhonda Lanford remanded2 a decision over the rezoning of a 144 unit apartment building back to the City of Madison.

The case was brought up by neighbors of the new development, who sought standing by anticipating future direct injury to their home by flooding caused by the new development. The standing was granted on the grounds that 1) the party would potentially be injured as a result of permits granted to build this apartment (not the rezoning that’s being argued) and 2) the permits are chained back to this initial rezoning legislation. At the same time, the plaintiffs’ attempts to reverse the rezoning decision were rejected because the City effectively did not consider the law when making this decision.

Specifically, § 66.1001(3)(k) and MGO § 28.003 required the City to make zoning decisions consistent with its plan but the record shows the City made this particular zoning decision based on other, immaterial factors. Essentially, this Court had no record to review that showed the city considered its plan.

If you did not follow the saga last year, many hours over many meetings were spent discussing stormwater management. There were underlying connotations around density, income, and multifamily housing, but not explicit comment as the decision got closer to Common Council. The focus was on the stormwater.

Plan Commission and City Staff provided technical analyses showing why the rezoning was appropriate based on the existing Comprehensive Plan. They also spent a lot of time discussing stormwater management systems to try and mediate concerns over flooding. Because the Plan Commission registrants for public comment heavily focused on the flooding, and because this decision is inherently political (Madison has elections over taxes and housing for the most part), the alders focused on appeasing the stormwater folks at Common Council. They did not explicitly acknowledge the analysis provided by City Staff and Plan Commission for why this rezoning was appropriate. As a result:

First, the City points to comments made during the plan commission and/or by the plan commission’s staff. Id. at 12-13 (citing Comm’r Solheim’s analysis at R. 490 and a “Staff Report at R. 579-90). The City’s citations to these comments is not helpful, however, because the City empowers its common council to make decisions about zoning amendments. MGO § 28.182(1).

Whether or not some other person analyzed the requirements of the plan, the City does not explain why that analysis might substitute for the council’s analysis, or lack thereof. In any event, the record does not support the proposition that the council was aware of the plan commission’s analysis, let alone that the council relied on that analysis to satisfy the requirements of its plan.

And:

Those remarks do not show the council applied the correct legal standard to its zoning decision because neither “the price of land” nor “the opportunity of residents to be heard” are relevant factors under the City’s plan. Once again, the City chose to create a plan that focused only on these factors:

[C]onsider the relationships between proposed buildings and their surroundings, natural features, lot and block characteristics, and access to urban services, transit, arterial streets, parks and amenities to determine if the context is appropriate for increased residential density. City Resp. Br., dkt. 13:11. (citing R. 571).

In sum, Western meets his burden to show the City proceeded on an incorrect theory of law by showing the city council never considered the factors it was supposed to consider according to its plan. The City’s attempt to show otherwise by focusing on selected comments by non- members of the council, or by Alders Rummel and Guiequerre, does not help its cause. If anything, those comments show the council preferred to base its decision on the cost of the land and/or the community’s opportunity to speak. The Court expresses no opinion about the wisdom of the City’s decision—what matters for purposes of this certiorari review is that § 66.1001(3)(k) and MGO § 28.003 required the City to make its decision “consistent with” a specific set of factors outlined in the city’s plan. The record shows the City did not do so.

I do not like lawyers or process. I understand why both are needed, but in many ways it’s just layer after layer of procedure that does not match the intents and purposes of what it constrains. Here are the questions I have as a result of this decision:

What is the purpose of Plan Commission or City Staff providing analyses if the alders seemingly need to do their own analyses or explicit acknowledgement of the analyses to make a decision?

What is the purpose of Plan Commission if Common Council ultimately has the final say on zoning matters?

What happens if it’s discovered that an alder intentionally did not make a decision based on the required factors? If an alder does not want a development to occur, can they throw out the entire decision or force constant remanding (further delaying the development) if they continually state on the record “I did not consider these factors when making my decision”?

How does one consider factors? Is it just a statement? Will we see alders go through the motions, reading a statement every time there’s a rezoning that establishes they reviewed and considered all factors? How does one establish intent?

This decision just adds more process to the process. At the end of the day, a developer obtained land and wanted to build a multifamily apartment complex. To build said apartment, the developer needed a rezoning and went through the process to legally obtain one. Plan Commission stated that this met Comp Plan requirements, alders probably reviewed those comments (at least the thoughtful ones!), and alders made the political decision to proceed with the rezoning despite small, local opposition. Stormwater management was heavily discussed, the developer brought forward plans to mitigate flood concerns voluntarily, and we all thought this was over.

This looks like a process that’s working. The Comp Plan allows for medium density buildings on arterial roads where there’s access to things like transit, schools, and grocery stores even if the zone is low-medium residential. This place meets all those conditions. These are the decisions Chuck talks about when he says we should (emphasis mine) “restor[e] local systems that are capable of acting on community values, not just responding to noise”. The community values, per the Comp Plan, are to build medium density in areas that make sense. But because of some procedural nonsense we had to redo the vote a year later and delay construction considerably. Abundance is right to identify these barriers as hurdles that we should get rid of, but is wrong in trying to remove them via a higher power. Instead, we should look to make those systems have less barriers. In this case, it means updating the Comp Plan.

How should we update Madison’s Comprehensive Plan?

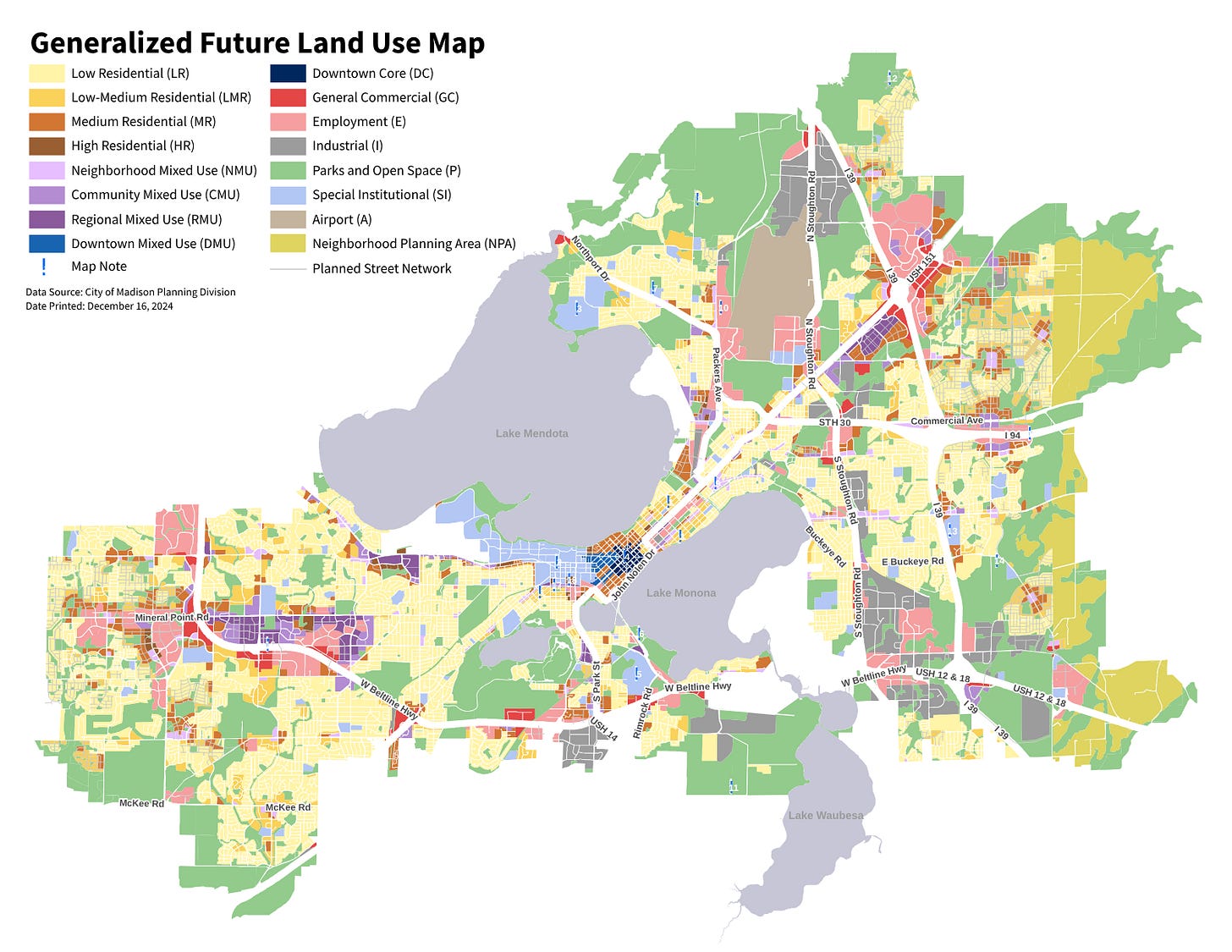

Wisconsin state law requires an update to the Comprehensive Plan at least once every decade. Madison breaks it down into five year cycles, where either the Comprehensive Plan or the Generalized Future Land Use (GFLU) map are amended. Because the Comprehensive Plan was last updated in 2018, the GFLU was updated in 2023 and the Comp Plan will be updated in 2028.

The Comp Plan is made up of nine elements. Cities must develop the plan by addressing each one. If a city does not address these nine elements, they will lose the ability to regulate their land. When cities attempt to amend zoning, subdivision, or mapping ordinances they must be “consistent” with the Comprehensive Plan. Consistent means:

[F]urthers or does not contradict the objectives, goals, and policies contained in the comprehensive plan.

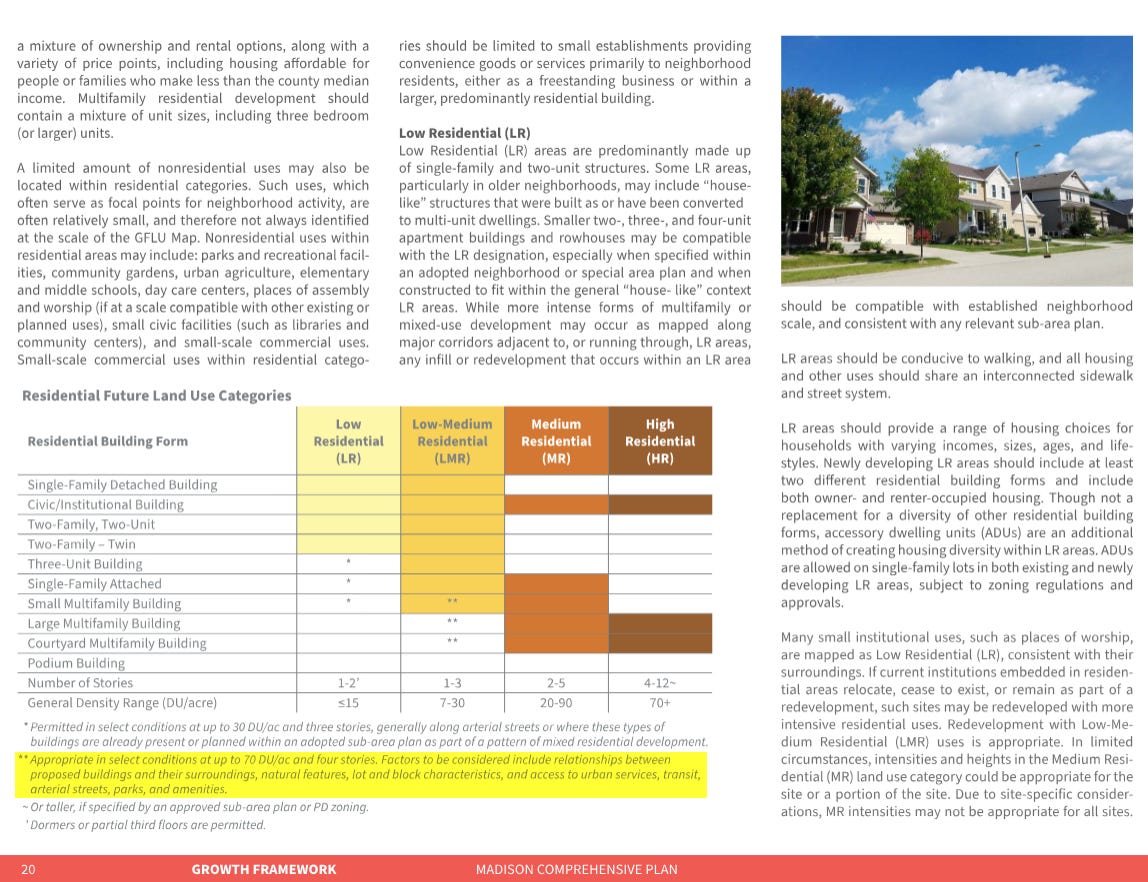

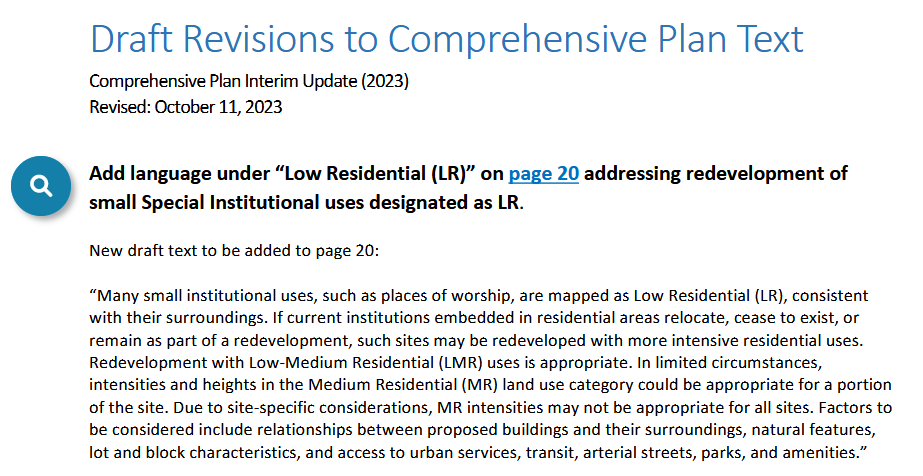

Madison’s Comprehensive Plan is 187 pages long. It is not entirely language that can be construed as law; it’s a fairly accessible document. But that length does expose it to potential discrepancies or language that can be interpreted in ways that are against the vision of the community (but for the vision of a few). To understand why this development was delayed, take a look at page 20:

The highlighted section of 42 words is (mostly) what got the City in trouble. How many more of these language tricks do lawyers have up their sleeves? How much exposure does the City have to delays because language that was intended to be helpful is misused and interpreted under the microscope of a judge, who views it from the wrong context?3

The Comprehensive Plan is an agreed upon, living document that the community provides input on and sees their elected alders confirm via vote. I believe now is the time to start drafting ways this document can be reformed to carry out the goals of the community for 2028. If we don’t try and accomplish our stated goals, why do we have a Comp Plan in the first place?

Because I’m not a lawyer, I can only grasp at straws for what the most effective language updates would be. Thankfully, there are lawyers that agree with the goals laid out in the Comprehensive Plan who can probably provide the correct advice. Considering this is less than three years away I think it would be best to get started now.

What does that mean for the rest of us?

If we can’t wordsmith, what can we do?

We can continue to show City Staff, who will end up writing this document, that people seek action and not just input. We want housing, safe streets, amenities, good schools, bike paths, bus shelters, awesome parks, snow plows, garbage pickups, and everything else in between. We see these themes come up time and again in Area Plan meetings and surveys. We can also see it with our elected officials, of which a majority helped co-sponsor and announce incremental housing updates with the Housing Forward 2025 proposals. These are the values that people are communicating and voting for, now is the time to make achieving them possible.

I’m reminded of staff comments on my proposed amendments in the 2023 GLFU revision process. In my attempt to try and remove large swathes of “Low Residential” land use and push it into “Low Medium Residential” my suggestions were not recommended. Even though, in my opinion, this amendment would:

Support development of a wider mix of housing types, sizes, and costs throughout the city

Increase the amount of available housing

Integrate lower priced housing, including subsidized housing, into complete neighborhoods

Support the rehabilitation of existing housing stock, particularly for first‐time home buyers and people living with lower incomes

These are all stated goals of the Comp Plan. It also helps these neighborhoods maintain form because specific parcels were already at higher density land uses. However, Staff said this was a “political decision”, the Area Plan process is a better forum, and the Transit Oriented Development overlay district already allows most of the parcels to go up to three units. There are many problems with this line of thinking!

First, not all alders are as technical as City Staff. Even if they understand what their constituents want, they might not know how to do that. If we dismiss suggestions4 as not in staff’s jurisdiction, without explaining why it would be better recommended at Common Council with an attached vote, it might require a savvy alder to actual get the community desired results. We’ve also seen in the Area Plan process that small groups of residents on the west side can hijack the input mechanism and remove the ability to get outcomes. Lastly, I’m tired of hearing that “something is already possible and that negates the need to change the law” when the same law says, in some interpretations, it is not possible or legal. We should either be consistent or preferably more general so we can’t be bogged down in legalese.

The cherry on top of this all? One of the recommended GFLU amendments from 2023 that did pass was the problematic section about Low-Medium Residential development and considering factors!

We need to prevent these own goals in the future.

I will borrow Chuck’s “slow, messy, and often invisible” but actionable levers that can help break the “paralysis all the way up” and lead to changes to the system:

Narrative dominance. Most communities have no alternative story about why the current system fails. Our job is to provide that story, clearly, repeatedly, and with examples that show what’s possible. When councilmembers start hearing the same questions from multiple directions—“Why are we blocking gentle density that aligns with our values?”—they start to feel the pressure shift.

Create visible wins. If the system won’t legalize ADUs by right across the board, help one homeowner do it as a pilot. Or find one that is grandfathered in and working well. Document everything. Turn the story into a column, a workshop, a visual. Sometimes the clearest path is to de-risk the unfamiliar by showing that it’s already working, quietly. The housing toolkit I shared with you is full or boringly normal people doing these things we want to ultimately seem boringly normal.

Strategic allyship inside the bureaucracy. You don’t need your entire staff to champion reform, just one or two mid-level staffers willing to help shape internal proposals, provide cost estimates, or identify the least risky way to get started. Celebrate their efforts publicly to protect them institutionally.

Feedback loops that don’t require council. Consider embedding reforms inside budget decisions, infrastructure maintenance plans, or administrative manuals. If you can’t change zoning directly, can you change how capital improvements prioritize walkable areas? Can you bake small wins into how staff scopes repairs?

Pressure from organized outsiders. Not state preemption, but organized citizen campaigns. If your commissioners and staff are stuck, outside groups (like a Strong Towns Local Conversation) can bring energy and legitimacy to the push. Don’t make it a demand for radical change; make it a call to implement the next smallest step.

We need to start pulling these levers, even if it’s exhausting, demoralizing, and painful5, to see the system change. I hope you’ll join me in helping make Madison a more prosperous and resilient place.

First referenced in “Joe Biden needs to avoid a return to ‘eat your peas’ budgeting” by Matt Yglesias, the idea is giving people what they want (ice cream). Abundance is making it so people can have what they want when they want it

Basically “sent back”

Probably for the right reasons, but that’s why law is so frustrating to me! It’s both black and white AND grey; it entirely depends on who’s interpreting it and how far

granted, there were over 80 amendments and lots of public comment

This other article from Chuck about his own neighborhood falling to the forces he’s spent over a decade fighting is heartbreaking. In some ways, it’s even an argument for the Abundance approach of moving decision making higher up the chain. But for that to work, you need to ensure the decision makers feel the same way and that’s a tough gamble. It would be easier to take this approach, but it’s risky. Change is hard, it takes time, patience, and nurturing, and that’s why I’ll look to all of you to help motivate each other to continue working towards our goals